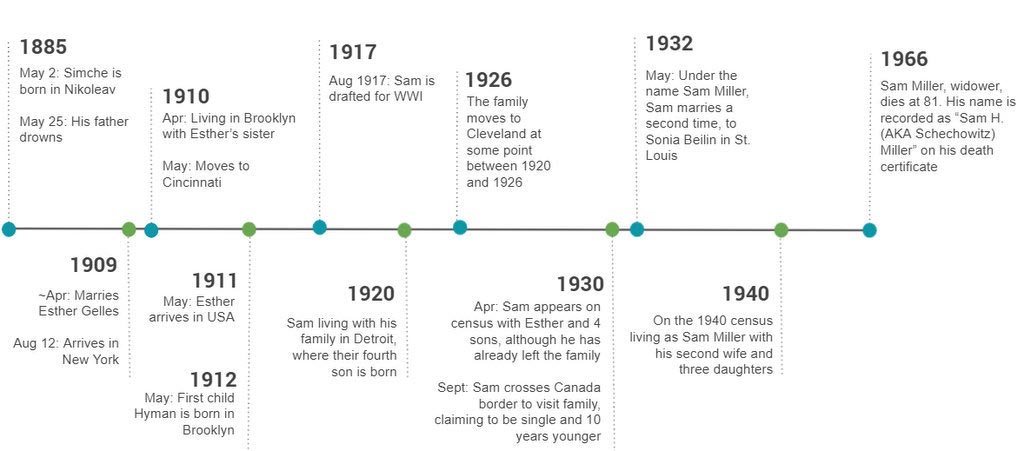

A lot of people had questions about Sam. His first family, who knew him as Sam Schechowitz, wondered what happened to him when he disappeared in 1929. His second family knew him as Sam Miller and they wondered about his past. Through DNA and genealogical research, I’ve been able to piece together much of Sam’s difficult history. In this post I’ll highlight the documents that I’ve found, the places I found them, and the questions that still remain.

Early years in the Russian Empire

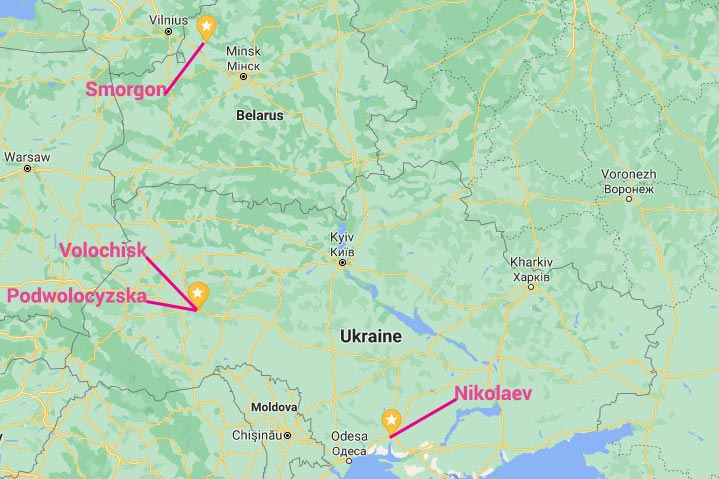

In 1882, Sam Schechowitz’s parents married in Nikolaev, a town on the southern edge of the Russian Empire in what is now Ukraine. His mother, Sheina-Pesya Malkin, came from a farming colony in Smorgon north of Minsk. His father, Chaim Schechowitz, was 33, more than twice Sheina-Pesya’s age, and came from Volochisk. Both Smorgon and Volochisk were from hundreds of miles away, but Sheina-Pesya’s family had settled in Nikolaev long enough to have had several children there.1

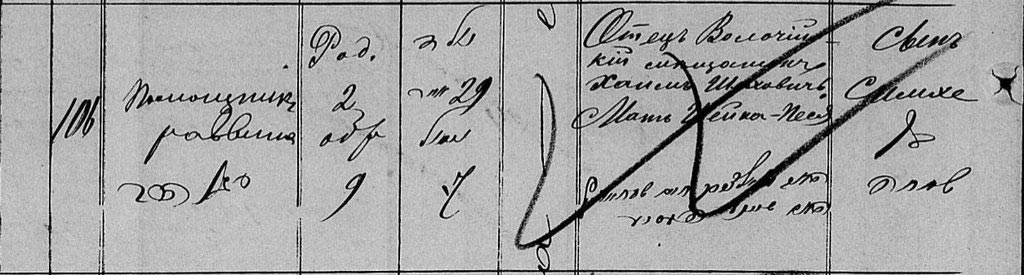

Less than a year later, the couple had their first son, Chaskel, named after Chaim’s father. On May 2, 1885 Sam was born, and was given the name Simcha. Just three weeks after Simcha’s birth, his father Chaim died at 35, a victim of what was recorded as “accidental drowning.” Sheina-Pesya was left a teenage widow with a toddler and an infant.2

Sam doesn’t appear in another record until 1909, when he emigrated to the United States at the age of 23. Before he left, he was conscripted into the Imperial Russian Army, where he served one year as a private. At the time the minimum term of service was six years, so like many young men in the Russian Empire, Sam must have deserted. This may explain why he had been living in Podwoloczyska, a town on the border of the Russian Empire, but on Austro-Hungarian side, and out of the reach of the Russian authorities. Podwoloczyska (now Pidvolochysk, Ukraine) was the sister town of Volochisk, the ancestral home of the Schechowitz family, and where his father was born.

Sam was newly married when he left Russia, but his wife, Esther nèe Gelles, stayed behind with her mother in Podwoloczyska. This sort of arrangement was not uncommon; men would often travel to the United States ahead of their wives, with the intention of making enough money there to send for their wives a year or two later.

On his passenger manifest Sam was recorded as a 5’6 painter with black hair and brown eyes. He said he was going to meet a cousin, Bere Feldmann, at 342 New Jersey Ave in Brooklyn, New York, and he arrived in New York with $20, which probably represented his life’s savings.

Unanswered questions: Why was Sam living in Pidvolochysk? How did he get across the border of the Russian Empire? When did he leave Nikolaev? And who was Bere Feldmann?3

Alone in America

Eight months after he arrived in New York, the 1910 census enumerated Sam living with his sister-in-law Annie Glazer (born Chana Gelles), her husband Harry, and their 1-year-old daughter in Brooklyn. The census recorded the following details on Sam: married one year, Yiddish speaker, unemployed building painter.4

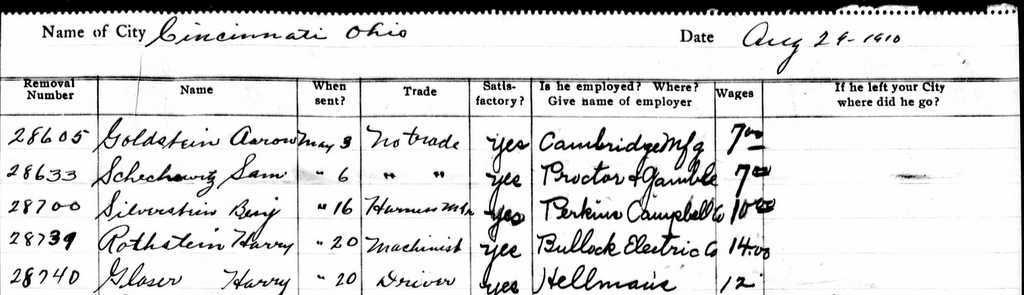

Just three weeks later, Sam pops up in the records of the Industrial Removals Office. The program, which helped relocate Jews from crowded East Coast cities to Jewish communities across the US and Canada, sent him to Cincinnati, Ohio in May, 1910. In their records, Sam was 24 years old and living at 745 Prospect, the same address as the census record and was recorded as having no trade. The column for whether the applicant was still in the city (Cincinnati) was left blank for Sam.

Unanswered questions: Why was Sam listed as having no trade when he was a painter? How long did he stay in Cincinnati?

There’s an IRO progress report for Sam dated August 29, 1910. He was recorded as working at Procter and Gamble in Cincinnati for $7 a week, and his employer considered him “satisfactory.” A few lines below him was Harry Glazer, the name of his brother-in-law, who was working as a driver at Hellman’s for $10 a week.5 Before he relocated, Sam was living with Harry and his wife’s sister, and it appears that the whole household had moved from Brooklyn to Cincinnati within a few weeks of each other.

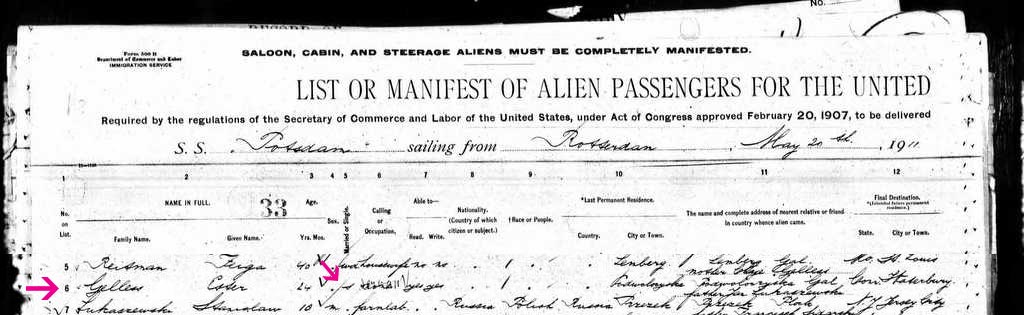

The next record is notable for the absence of a mention of Sam. On May 31, 1911, his wife Esther arrived in New York using her maiden name, Gelles, and reported that she was single on the passenger manifest. She provided her mother’s name in Podwolocyzska as her contact person, and was going to meet her cousin Sam Spirt in Waterbury, Connecticut.

And here we have a lot of unanswered questions: Why was Esther traveling under her maiden name and going to meet her cousin instead of her husband? Where was Sam?

Together again: Starting a family

The next two records make clear that Sam had reunited with his wife and moved back to New York. Their son Hyman was born in Manhattan in May, 1912 (his Hebrew name was Chaim, and he later went by the more Americanized Herman). A daughter, Pessie, was born on April 23, 1914, and then died 6 days later at 56 Seigel Street in Brooklyn. The cause of death was “Septic umbilical infection with extension to surrounding cellular tissue and peritoneum, from lack of cleanliness.”6

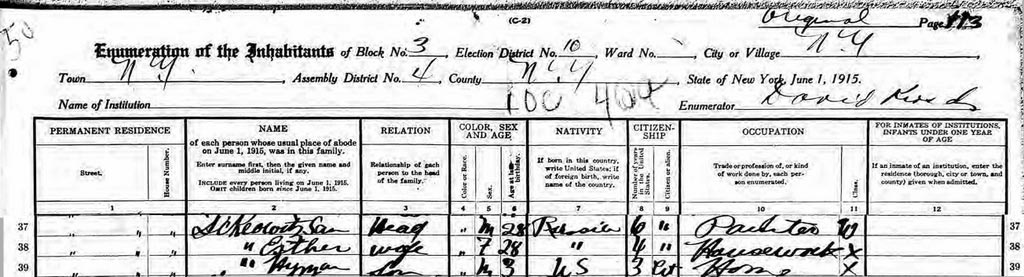

In the 1915 New York State Census, Sam, Esther, and their son Hyman were back in Manhattan, living at 70 Willett Street on the Lower East Side. Sam worked as a painter, and was recorded as being a 28-year-old alien who was born in Russia and had been in the United States for 6 years.

Two more sons were born: Saul in Manhattan in 1915, and Michael in Brooklyn in 1917.

The mysterious years

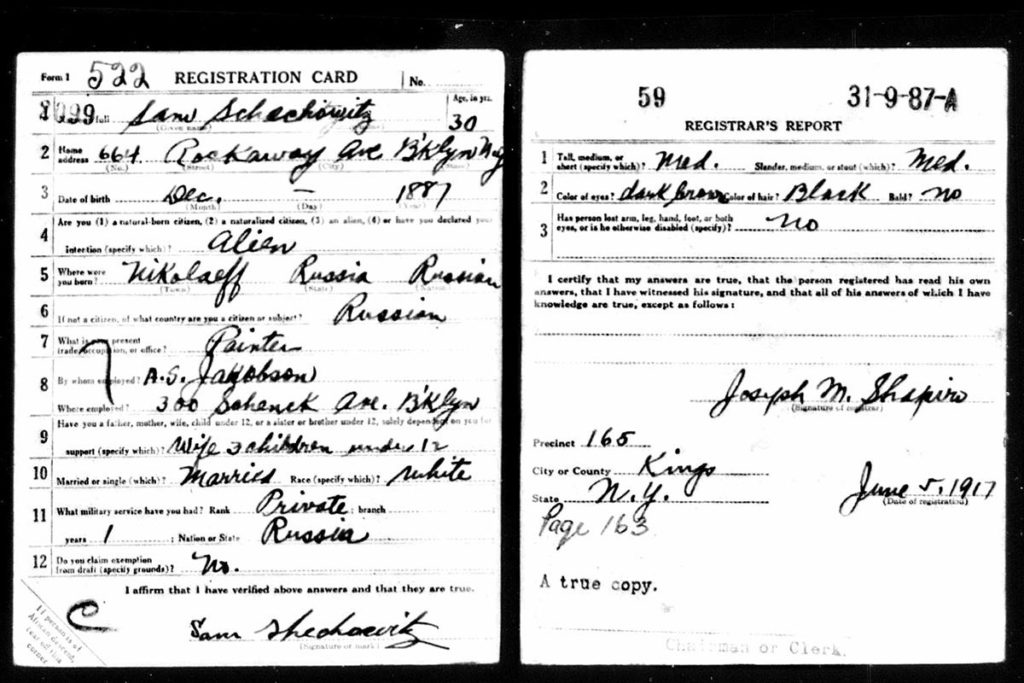

In June, 1917, Sam filled in his WW1 draft card under the name Sam Schechowitz, 664 Rockaway Ave, Brooklyn. He said that he was not naturalized, born December, 1887 in “Nikolaeff, Russia,” and mentioned his stint in the Russian army. He included the information that he was married with three children under the age of 12 who were dependent on him, presumably hoping to get out of military service.

Two months later, the Brooklyn Standard Union printed a list of men who were called into action. “Schachowitz Saml, 664 Rockaway Ave” appears on the list. A second list of men who “failed to appear, certified for service” was in the next column. “Schechowitz, Sam, 664 Rockaway Ave” appears there, too.7

During this period, Sam’s life seems tumultuous. On every record the family has a new address, even when the records are only a few months apart. They moved between Brooklyn and Manhattan several times, suggesting they didn’t have roots or a community in either place. Esther had several siblings in the United States, but by 1917 all of them had left New York. Their daughter Pessie’s death in 1914, which could have been prevented by better hygiene and access to medical care, was a clear sign of poverty.

And this is where things start to get confusing…

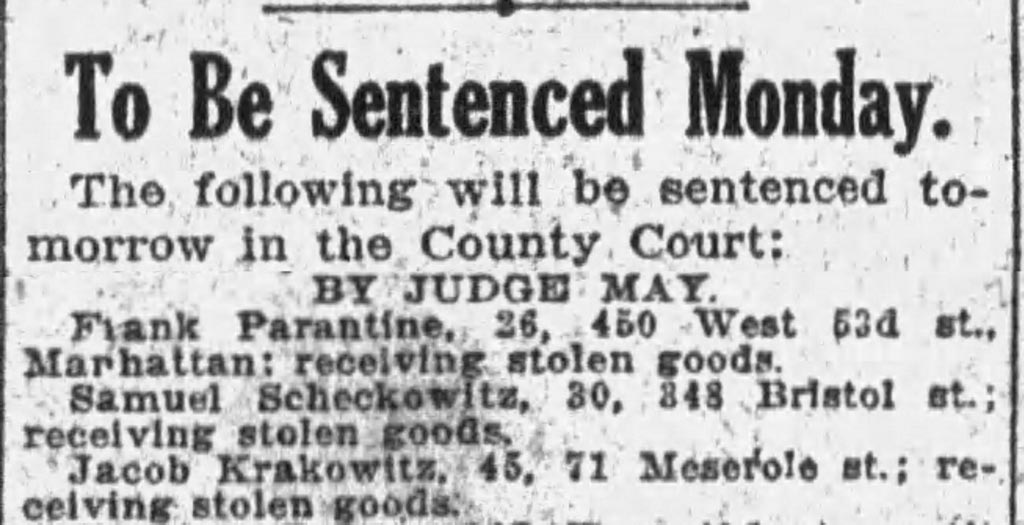

Between January and March of 1918, there were three articles in the local newspapers about a robbery that took place in Brooklyn on January 17th at Isaac Partnoy’s tailor shop. The police stopped two men driving a wagon, and when the men jumped down and ran off, the police fired shots. Despite putting up a “stubborn resistance” the men were eventually caught, and the police found the stolen rolls of cloth in the wagon. One of the men was Samuel Scheckowitz, 30, of 348 Bristol Ave. In March a newspaper article reported that he would be sentenced for receiving stolen goods the following day, but I have not located a record of the sentence.

Now, there’s no evidence tying “our” Sam to this robbery, but it’s an uncommon name with no other likely candidates. Using the December 1887 birth date he gave on his draft record six months earlier, Sam would be 30, and 348 Bristol Ave was a block away from Sam’s last known address of 664 Rockaway Ave.

From here on out, Sam remains mostly out of the records. His son Solomon was born in Detroit in 1920, but I haven’t been able to find the family in the 1920 census in Brooklyn, Detroit, or Ohio. In 1926 he was recorded in a City Directory in Cleveland, listed as a painter.

Unanswered questions: Did Sam commit this robbery? Did he end up serving in the US Army? This question becomes more important later…

One last appearance…

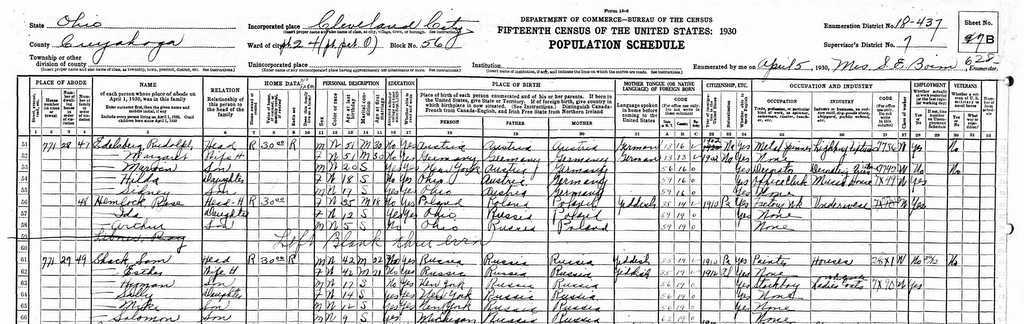

Sam appeared on the 1930 census as Sam Shack with his wife Esther and four sons in Cleveland, Ohio. He’s listed as being 42, a Yiddish-speaking house painter, and having registered his first naturalization papers. But he may not have actually been living with his family at the time the census was taken. According to one of his grandchildren, Sam left the family several times, and then left for good in 1929.

Unanswered questions: Did Sam actually file a Declaration of Intention? Where?

In September of 1930, Sam Schechowitz, 36, and single, crossed the Canadian border at Niagara Falls. Our Sam would have been 45 and married, so was this really him? He’s listed as a Jewish painter, from New York, born in “Nicolieff, Russia,” and his nationality was listed as “cl.USA” He’s going to visit his uncle Dave Spector in Toronto and gives an aunt, Rebecca Anten in Richmond, Virginia as his contact person.8

Our Sam Schechowitz did have relatives named Dave Spector and Rebecca Anten. After extensive and time-consuming research that I will not bother detailing here because it will add another 3,000 words, I confirmed that Sam’s mother, Sheina-Pesya Malkin, had several siblings who had emigrated to the United States. Rifke, later called Rebecca, married Israel Anten and lived in Virginia. Another sister, Leah, married David Spector and moved to Canada. Just a month before Sam listed Leah’s husband on his border crossing document, she died at age 51 in Toronto. Perhaps Sam was visiting her widower and six adult children to pay his respects.

Unanswered questions: What was Sam’s citizenship status, what does “cl.USA” mean, and why can I find no record of him returning to the United States?

This is the last mention of Sam Schechowitz I could locate. The trail went cold. I learned that when he abandoned his family his two youngest sons, who were 9 and 12, had to be surrendered to foster care, and his wife Esther must have suffered immeasurably. She died in Cleveland in 1942 at the age of 54, her death hastened, no doubt, by the stress of living through the Great Depression with no means to support herself and her children. Neither she nor her four sons ever heard from Sam again.

Life as Sam Miller

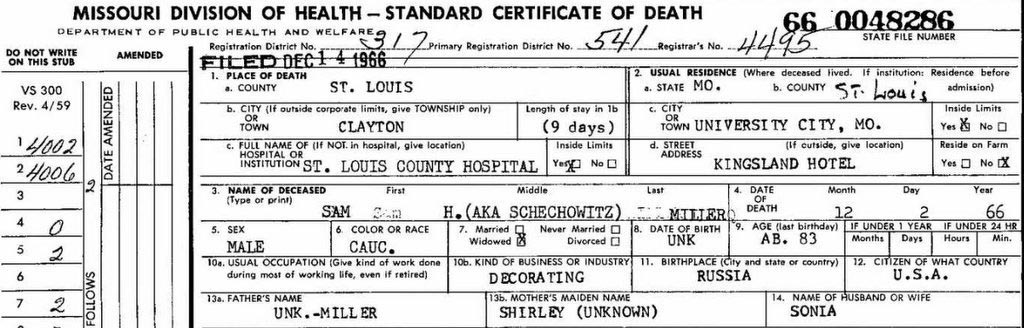

And then… I was searching for various spelling variations of Scheckowitz and Schechowitz as I often do (that’s a whole other story), and came across a death record on Ancestry for a Sam Miller in Missouri. Who’s Sam Miller? Maybe this record got re-indexed recently, because here was a death record for Sam Miller that said “Sam H. (aka Schechowitz) Miller.”

As I dug into the life of Sam Miller, a painter in St. Louis who mysteriously appeared around 1932, I became increasingly suspicious that I had found our Sam. I knew, though, if I could find evidence of Sam Miller existing before 1930, that this probably was a different guy. So when I found him on his great-granddaughter’s family tree on Ancestry with no early history and the label “brick wall” attached, my heart skipped a beat.

I contacted her, explained my suspicions, and asked if I could view her mother’s DNA matches. And there it was — Sam Miller’s granddaughter shared a 550cM match with Sam Schechowitz’s granddaughter, almost the exact average amount listed for Jewish half-first cousins on Lara Diamond’s Ashkenazi average shared DNA chart.

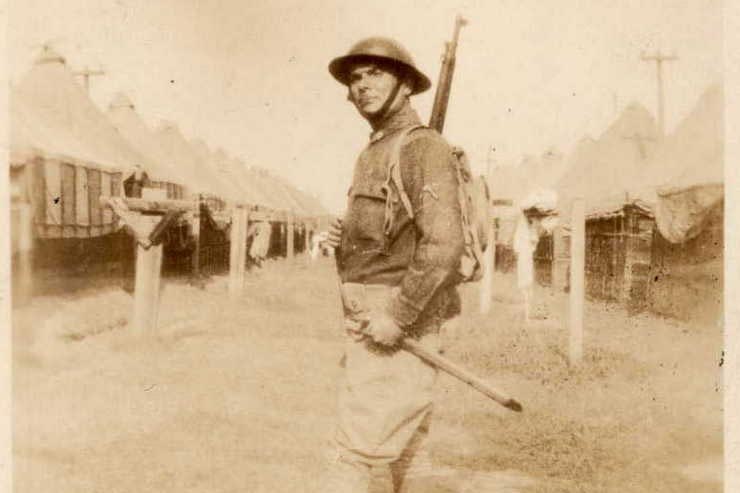

She sent me a photo of Sam in the army, which she assumed had been in Russia, where the family knew he had spent some time in the “tsar’s army” (and Sam Schechowitz did spend a year in the Russian army). When I had the photo dated by military enthusiasts on Reddit, they identified it as very clearly American, and taken circa 1917 or 1918 based on the M1917 helmet.

Unanswered questions: Where was the documentation of Sam Schechowitz serving in WW1? Is it possible that if Sam committed the robbery, that he was sent to the army to fulfill his draft obligations?

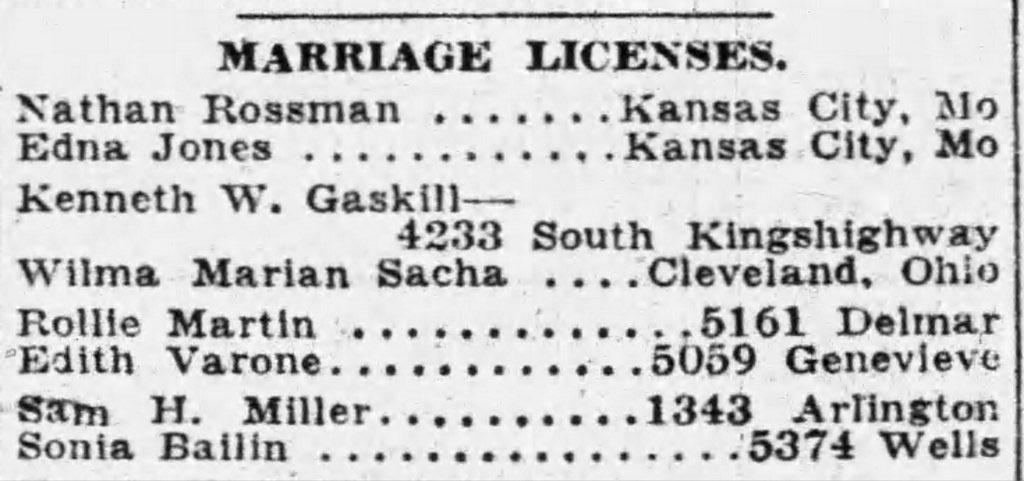

Sam Miller appeared in St. Louis, Missouri sometime around 1932. The first certain record of him was a notice in the St. Louis Globe-Democrat on May 22nd of a marriage license being issued for “Sam H Miller of 1343 Arlington and Sonia Bailin of 5374 Wells.”9

Sonia was 23 when she arrived in the United States from Gomel, Belarus in 1930. A HIAS client, she traveled with her older sister to meet a cousin in St. Louis with whom she was still living when the marriage license was issued.

At the time of their marriage, Sam was twice Sonia’s age, much like his own parents.

Unanswered questions: What does Sam and Sonia’s marriage license application say? Was he previously married? Who were his parents? I’m waiting to hear back from the St. Louis Recorder of Deeds to find out…

A little more than a year after they were married, Sam and Sonia’s first daughter was born on July 4, 1933, when his youngest son from his first marriage had just turned 13. Sam and Sonia’s second daughter was born in 1935, and their third in 1936.

His first family was all boys, and now, all of the children in his second family were all girls. How much did the girls know about Sam’s former life? His great granddaughter told me that one of the little tidbits of information that the children knew about Sam’s former life was that he had lived in New York before moving to St. Louis, and that while working as a painter he had possibly painted an opium den.

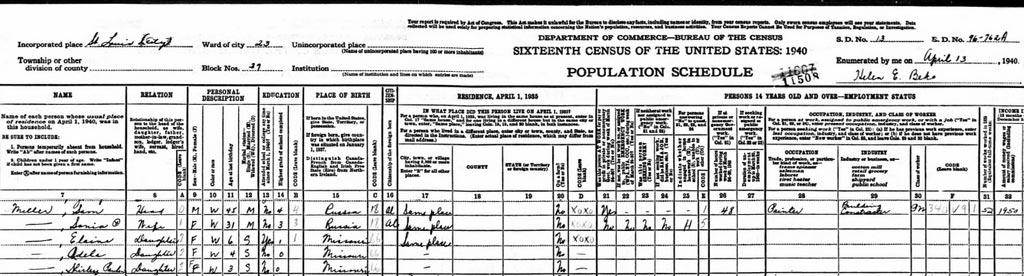

On the 1940 census, Sam Miller was living with his second wife and three daughters. He’s recorded as being 45 (he was actually 55), born in Russia and both he and his wife are listed as aliens, meaning they had not naturalized as American citizens. The census also recorded that Sam worked for 48 hours the prior week as a painter. If nothing else, it appears that Sam was providing for his second family in a way that he wasn’t able to for his first.

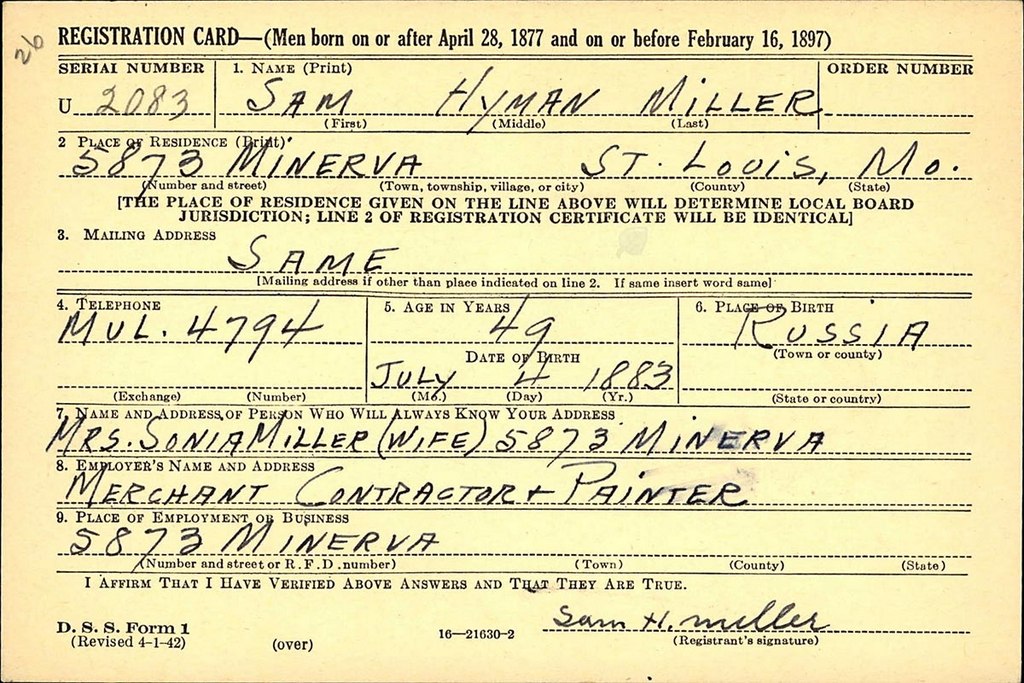

On his 1942 WWII draft card he’s listed as Sam Hyman Miller, born on July 4, 1883 in Russia. His occupation was given as “merchant contractor and painter.” Sam was nearly 60 at this point, and his hair was starting to grey, and he had put on weight; he was recorded as being 164 pounds with a ruddy complexion.

His birthdate of July 4 also happens to be that of his first child from his second marriage. Did he adopt hers when needing to come up with a birthdate on the spot, or did he choose the famous American holiday as many immigrants did? His middle name, Hyman, which he had adopted as part of his new identity was a variation of his father’s name, but also his oldest son’s name, the son whom he hadn’t seen or talked to in more than a decade. I wonder if he thought of his first family whenever he wrote down his middle name, and how he might have rationalized deserting them.

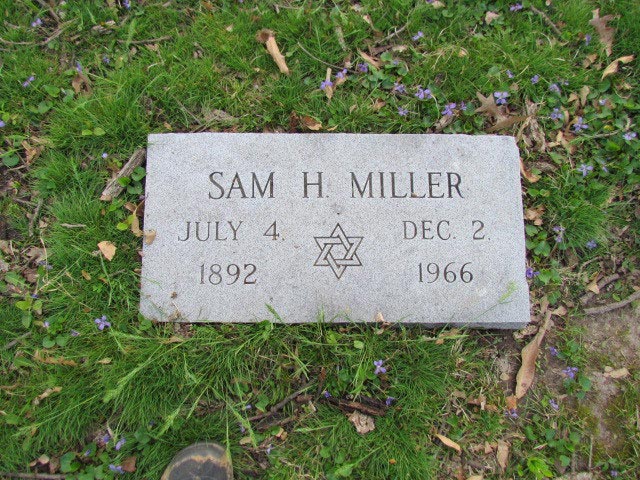

Sam Miller died in 1966. At the time of his death he was a widower, living at the Kingsland Hotel in St. Louis. On his death record, his daughter Shirley Pauline gave his name as “Sam H. (aka Schechowitz) Miller.” His mother’s name was also listed as Shirley, and it seems likely that Shirley Pauline was named for his mother, Sheina-Pesya.

His daughter knew of his former name, but the family believed that he, like many immigrants, changed it soon after his arrival in the United States to sound more American. Did they know he had a previous life under the old name? That they had four-half brothers? I wondered why his daughter Shirley decided to have his former name included on his death certificate. Scores of immigrants Americanized their names after settling in the United States, but it was not common practice to include their former names on their death certificates. Did his daughter have some inkling of his former life? Whatever her motivation, it was her attention to detail that made it possible to connect the two halves of Sam’s life for the first time.

All of Sam’s children have passed, and few memories remain of him. From his first family, the memories that survive are painful and filled with hurt. I was told, “The deserted family knew little and spoke less about Sam.” From his second family, the memories that were passed down are positive, but spare. He is remembered as a sweet man, who was good to his grandchildren.

I don’t know much about Sam’s life beyond what I’ve found in the records. I do know that Sam Schechowitz disappeared from his family in 1929 or 1930, and after that, despite extensive searching, I can find no further record of him. And I know that Sam Miller appeared in St. Louis in 1932, and that apart from a photo of him in the military, there seem to be no records of his life before that year. I believe that his death record, with information from his daughter that ties both of these names to the same man, and the DNA evidence which clearly links his first family and his second family, show that Sam Schechowitz and Sam Miller are one and the same.

I know that this research can’t provide closure to the families involved, but I hope that at least it can answer some questions that they thought would never be answered. I am very grateful for all the members of Sam’s family, on both sides, who have helped me put together the pieces of this puzzle.

Nikolaev is now Mykolaiv, Ukraine, Volochisk is Volochys’k, Ukraine, and Smorgon is Smarhon, Belarus. ↩

I found Simcha and his brother’s birth indexed on Jewishgen. I found the marriage and death records via searching the index at Miriam Weiner’s Routes to Roots site, then using that information to find the unindexed records on Familysearch. ↩

Feldmann may be a cousin of Esther Gelles. When Esther’s sister Chana arrived in NY in 1906, she listed her contact person as “cousin Leon Feldmann at 957 Myrtle Ave Brooklyn” ↩

Passenger manifest and 1910 census found on Ancestry. Passenger manifest for Esther and her siblings found by using the “Gold Form” at Stevemorse.org. ↩

Records found by following the advice in a talk called “Why Did They Go There? Finding Answers in the Records of the IRO” by easterneuropeanmutt.com: search the index at CJH and then find the unindexed record on Ancestry. ↩

I found Sam’s sons in the NYC birth index on Ancestry, his daughter’s death on Familysearch and the cause of death from an Ancestry transcription. Family History Centers are closed due to covid, but normally I would try to get a full copy of the death record there. *update, I got the full record (Brooklyn death record dated April 14, 1914 for Passie Schechowitz, no. 9162) and the transcription was correct. ↩

Newspaper clipping from Newspapers.com. ↩

I found a mention of this border crossing on Ancestry, but the manifest was blurry. I found a better copy on the Canada Library and Archives site. ↩

From St. Louis Globe-Democrat, St. Louis, Missouri, 22 May 1932, Page 26 found on Newspapers.com ↩