A few weeks ago I came across this story from the October 23, 1915 issue of a German weekly, Die Woche. It’s a travelogue of a visit to Przédborz written by Dr. H. Roesing, believed to be Dr. Lieutenant Roesing of the German Royal Wuertemberg Army Corps. It’s a fascinating look at pre-war Przédborz and its Jewish community, infused, of course, with the prejudices one might expect.

In trying to learn more about this piece, I found a PDF translation on Sam Ginsberg’s amazing site about the stamps of Przédborz. I immediately sent him an email, and only discovered this morning that unfortunately Sam passed away a few months ago. Sam’s site is a treasure trove of information about Przédborz; initially it focused on the philatelic history of Przedbórz and how to identify forged Przédborz stamps (which are apparently quite common). Over nearly a decade, Sam expanded the site to cover much more about the town and its Jewish history. I’m very grateful to Sam for his research, and I hope his family keeps the site online.

I’m republishing here the translation by James A.M. Elliott of the travelogue by Dr. H. Roesing with an introduction by Sam Ginsburg here. (James, if you come across this, I’ve been trying to find you!)

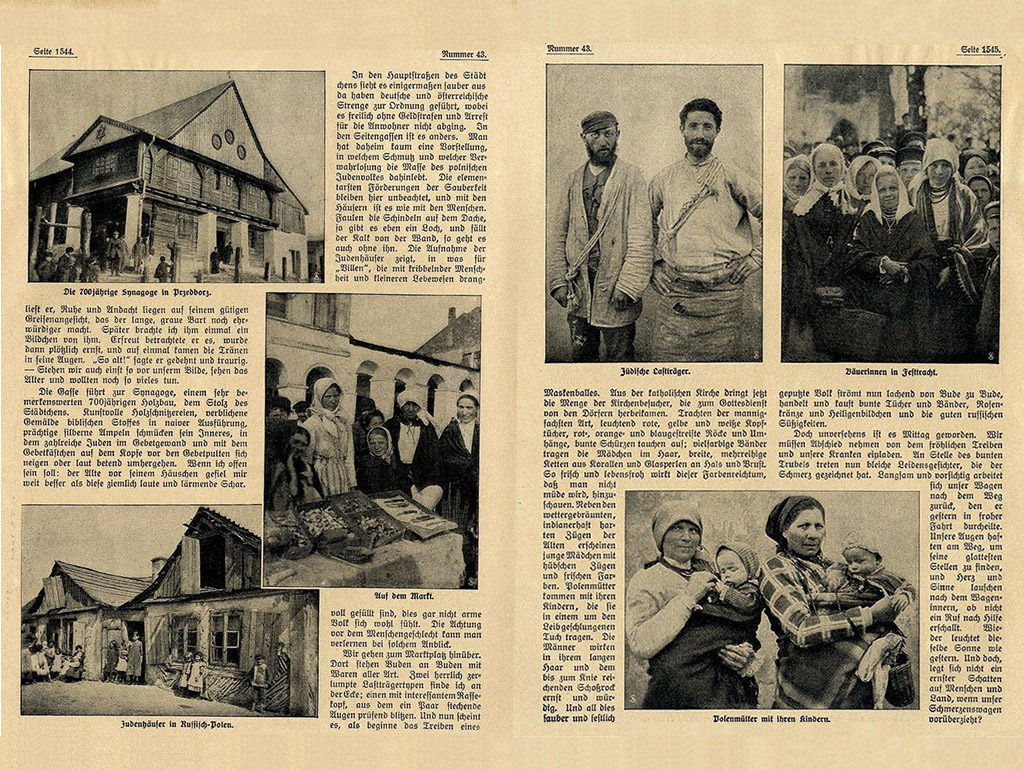

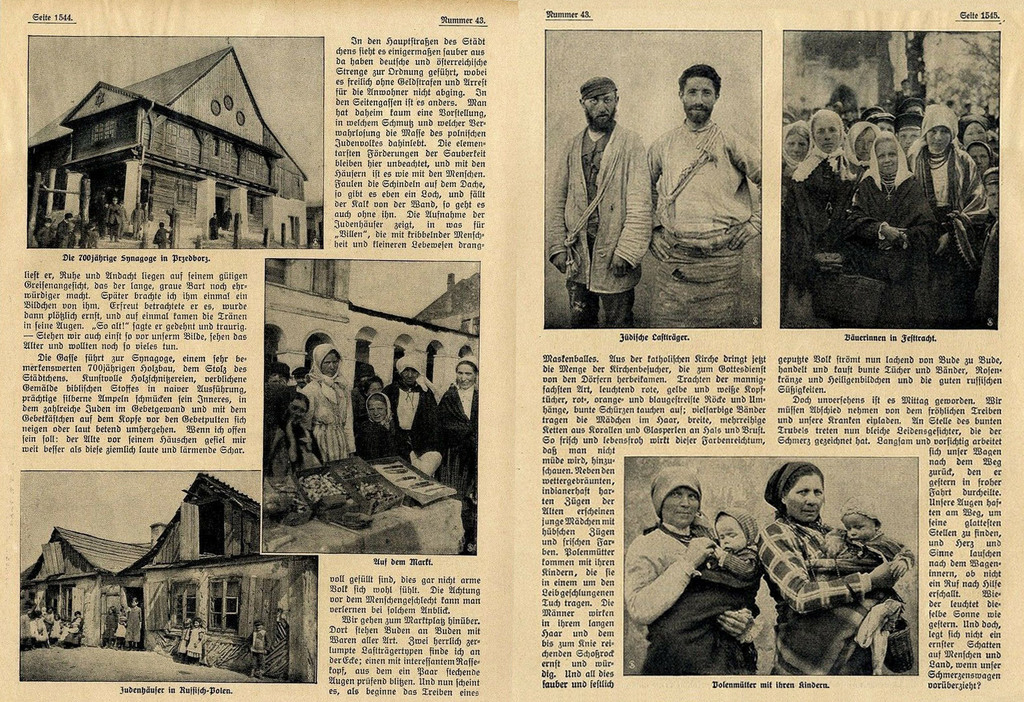

“700-year old Jewish Synagogue in Przedbórz”

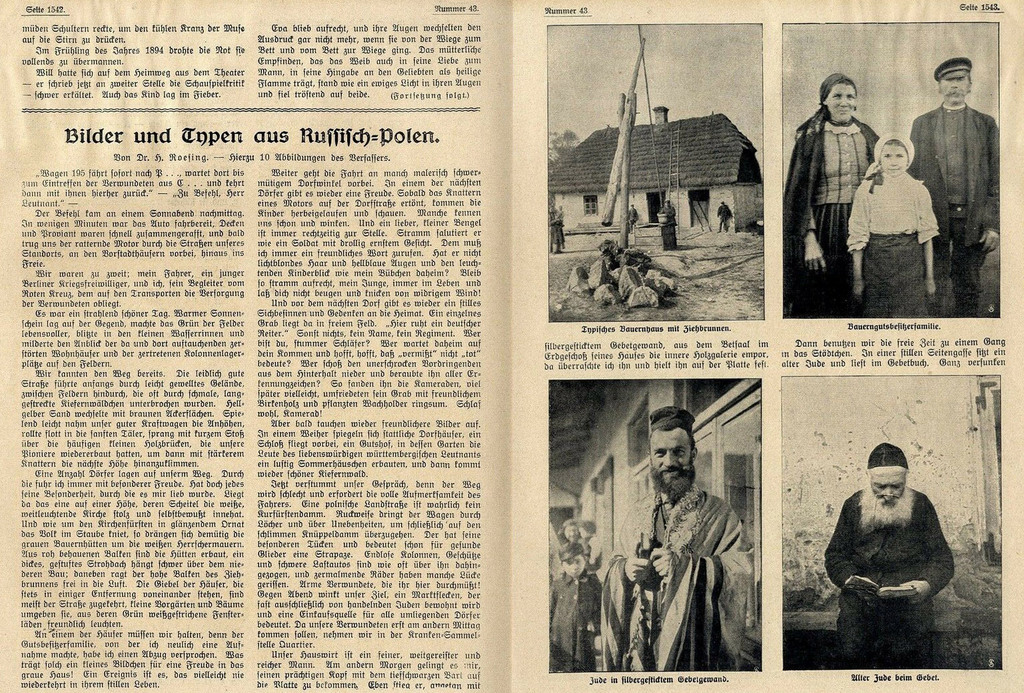

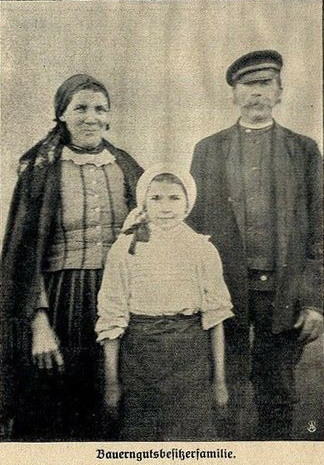

“Polish Mothers”

A 1915 Visit to Przedbórz…Introduction by Sam Ginsburg

This article, or rather travelogue, was originally written by one Dr. H. Roesing, and published in the 23 October, 1915 issue (#43) of Die Woche, a German weekly that seemed to like articles of this sort. Roesing’s original title was “Bilder und Typen aus Russisch=Polen” (“Pictures and Human Types from Russian-Poland”). We believe the author is the same Dr. Lieutenant Roesing assigned to the German XIIIth Royal Wuertemberg Army Corps.

Przedbórz, Poland is located on the east bank of the Pilica river about 110 km north of Kraków. It had been part of the Russian Partition since the Treaty of Vienna in 1815. Its renowned wooden synagogue is prominently featured in Heaven’s Gates, Wooden Synagogues in the Former Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, by Maria and Kazimierz Piechotka (2004). Przedbórz is also known for 18 local delivery stamps it issued in 1917-18, and which are often still in wide philatelic demand.

During WWI, the Russians were initially attacked in Przedbórz by the Hungarian 31st Nagyszeben Infantry Regiment on 17 December 1914. Fighting continued in or around Przedbórz until approx. 25 February 1915, when the Russians were permanently driven out, and the town came under the jurisdiction of the Austrian military.

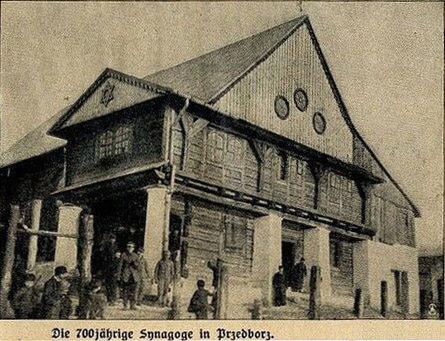

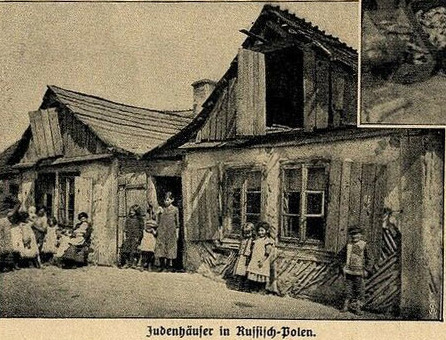

“Jewish Houses”

A 1915 Visit to Przedbórz By Dr. H. Roesing

(Bilder und Typen aus Russisch=Polen) Translation by James A.M. Elliott

”Car No. 195 goes at once to P … waits there until arrival of wounded from C …. and then returns with them. At your service, Lieutenant, Sir.”

The order came on a Saturday afternoon. In a few minutes the car was ready for travel. Blankets and provisions were quickly pulled together and soon the clattering motor was taking us through the streets of our garrison, passing by the houses of the suburbs, out into the open. There were two of us, my driver, a young volunteer from Berlin, and me, his companion from the Red Cross, whose responsibility it would be to care for the wounded.

It was a lovely sunny day, the sun’s rays streaming down. Warm sunshine blanketed the area, making the green fields livelier. The sun’s light flashed in the little gullies, softening the sight of the destroyed houses cropping up here and there and the treaded-down areas of the fields columns of troops had tramped over.

We knew the way already. The reasonably good road led initially through gently undulating terrain gradually rising, through fields, often broken up by narrow, extended strips of pine woods. Bright yellow sand alternated with brown acreage surfaces. Motor lightly straining, our good motorcar took the rises easily, rolled along as if floating in the gentle valley, sprang with a tug over the frequent small wooden bridges that our pioneers (military construction corps) had rebuilt. Then, with stronger clattering of the motor, the vehicle climbs up the next steep rise.

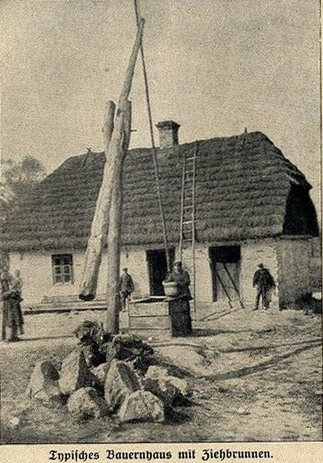

A number of small villages lay on our way. Through them I have driven always with special joy. For each one has its own peculiarity – something special about it through which it endears itself to me. This village there lies on a hill whose summit is occupied by a white church, gleaming in the sunlight far and wide, proud and self-aware; and just as around a prince of the church in his bright finery the people would kneel in the dust, so do the peasants’ gray huts humbly press up around the white master walls. Out of rough hewn timbers the houses are built, a thick, stepped, roof of straw hanging heavily over each low building; next to the dwelling the tall beam of the draw-well towers free in the air. The houses’ gables, that are always set some distance apart from one another, are mostly turned toward the street; through the small front gardens surrounding them, white painted window shutters shine brightly.

At one of the houses we must make a stop, for I have promised the owner of the property, whose picture I took recently, a print. What joy such a little picture brings into the gray house! Such an event! It is an event that perhaps will never recur in their quiet life!

The trip goes on further; by many a picturesque, melancholy village corner. In one of the next villages, yet again a joyous experience awaits. No sooner than the clatter of the motor is heard on the village streets, the children come running and look. Many a one of them knows us already and waves to us. And one darling little boy is always there, every time we arrive; standing straight at attention and saluting like a soldier, a drolly earnest expression on his face. To him I must always call out a friendly word. Hasn’t he light blonde hair and bright blue eyes and a beaming child’s expression, just like my little boy back home? Stay so, standing straight and upright, my boy, always in life, and don’t let yourself be whipped and pushed about by contrary winds.

And just before reaching the next village, again an occasion for reflection and remembrance of the homeland. A single grave lies there in the open field: “Here rests a German cavalryman.” Otherwise, nothing: no name, no rank, no regiment. Who are you, silent sleeper? Who waits at home for you, and hopes that “missing” does not mean “dead?” Who shot down the intrepid rider from some ambush and robbed him of all means of identification? So his comrades found him, after quite some time, perhaps, and buried his remains; they fenced it with bright, cheerful birch wood and planted it around with juniper. Sleep well, Comrade.

But soon appear again more cheerful sights. In a pond are reflected stately village houses; a castle flies by, a country estate in whose garden the people the amiable Wuertemberg Lieutenant built a jolly little summer house. Then again come pretty pine woods.

Now our conversation falls silent, for the road turns bad and requires the full attention of the driver. A Polish country road is no Kurfuerstendamm (King’s Highway). Jerkily, in fits and starts, the car forces its way forward through holes/ruts and over bumps in the rough uneven surfaces, finally going over the bad corduroy road. The corduroy road has its own treacherous spots, and means even for healthy limbs harsh physical punishment. Endless columns of troops, guns, and heavy trucks and vans have gone how often over this road, and crushing wheels have torn gaping holes. Poor wounded ones, who must traverse this stretch.

Toward evening, our destination beckons, a small market town that is almost exclusively inhabited by Jewish traders, and constitutes a source of purchases for all the surrounding villages. Since our wounded may be coming as early as around noon tomorrow, we take up our lodgings in the part of town where the assembly point area for the sick and wounded is located.

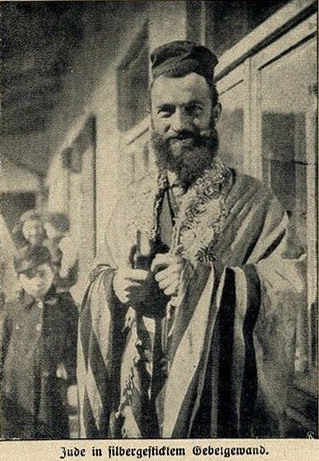

Our landlord is a refined, widely travelled, and wealthy man. Next morning, I succeed in capturing on the photographic plate his magnificent head with the dark black beard, just as he was climbing up [to] the inside wooden gallery, in his silver knitted prayer shawl, from the prayer room on the ground floor below, I surprised him and captured his image on the plate.

Then we used our free time to take a walk into the little city. In a quiet side street an elderly Jewish man is sitting and reading in his prayer book. Entirely absorbed, he reads, peace and reverence on his kindly old man’s face that his long gray beard makes even still venerable. Later I brought him a little picture of himself. Joyfully he gazed at it, then turned suddenly solemn, and all at once tears came to his eyes. “So old,” he said, slowly and sadly. So it is, that one day we stand before our picture, see our age, when yet we had wanted to do so much.

The side street leads to the synagogue, a very noteworthy 700 year old wooden construction, the pride of the little city. Artistic wood carving, faded paintings of biblical subjects, splendid silver lamps, decorate the interior, in which are gathered many Jews in prayer shawls and phylacteries on their heads, inclining themselves at the prayer desks, or praying loudly and walking around. To speak frankly, the old man in front of his little house pleased me far more than did this quite loud and wailing crowd.

In the main streets of the little city it looks to some extent neat and clean. Naturally it must be the German and Austrian strictness for order that has led to this result. It was not brought about without, of course, some imposition of fines and arrests. Off the main way, in the side streets, it is quite otherwise. Back home one has hardly any notion, in what dirt and lack of maintenance the mass of the Polish Jewish people live. The most elementary demands of cleanliness remain unobserved here, and with the houses it is as with the people. If the shingles on the roof rot away, so there is a hole, and if the limestone falls from the wall, the wall goes without it.

The picture of the Jewish houses shows in what kinds of “villas,” filled to the brim with bustling humanity and smaller beings, these people, who are not poor, feel at home.* Such a sight can almost lead one to forget one’s respect for humankind.

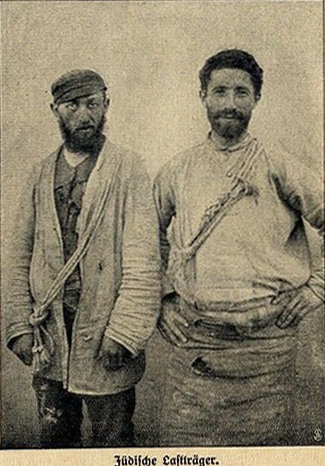

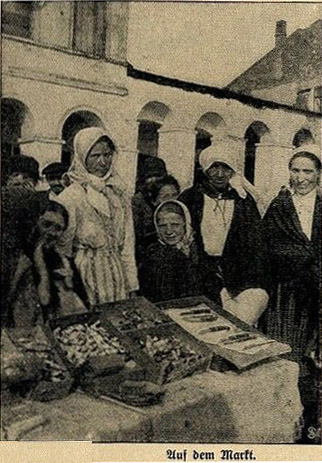

We walk on further, over to the market place. There stands booth after booth, with wares of all sorts. I find two splendid porters in ragged clothing standing at the corner; one with an interestingly classic face typical of his race out of which two sharp eyes flash searchingly.

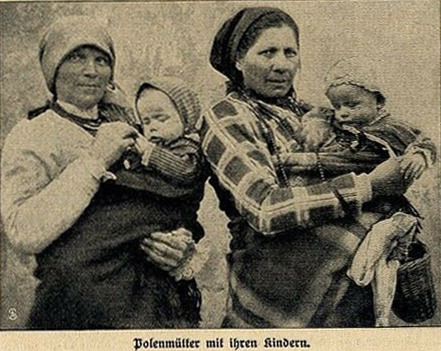

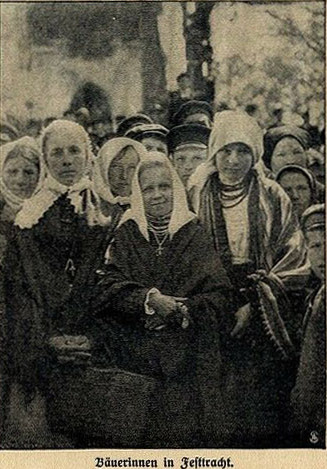

And now there seems to begin the hustle and bustle of a masked ball. Out of the Catholic church stream quantities of visitors, who have come from the surrounding villages to attend services. Traditional costumes of the most variegated kind, reds, yellows and whites gleaming brightly in the sunshine; scarves, red-, orange- and blue striped coats and cloaks, bright aprons make their appearance; multi-colored ribbons are worn by the young women; wide, multiply rowed necklaces with coral and glass pearls adorn necks and bosoms. So fresh and lively is the effect of this kingdom of colors that one does not weary of looking at it. Beside the weather-browned Indian-like, hard features of their elders, appear young women with pretty features and fresh forms. Polish mothers come carrying their children held in slings around their bodies. The men look serious and dignified with their long hair and in their coats reaching to the knees. And all these festively attired people now stream, laughing, from booth to booth, trading, and buying colored cloth and head bands, rosaries and pictures of saints, and good Russian sweets.

But unnoticed, in less than no time, it has become mid-day. We must leave the happy bustle, and take on board our invalids. In place of the colorful throng, now enter the pale, suffering faces etched by pain. Slowly and carefully, so as to find the smoothest way, our car works its way back along the road along yesterday it had travelled rapidly, and now heart and mind listen to the interior of the ambulance, in case a call for help rings out. Again shines the sun, the same as it did yesterday. And yet, does there not lie a solemn shadow on people and land, wherever our pain-laden vehicle passes by?

*This is an alteration of the original translation by James A.M. Elliott, which read “The photograph of the Jewish houses shows in what “villas” – crammed full with swarming humanity and lesser forms of life – this definitely not poor people feel comfortable.”

Jim Elliott is a retired economist whose interest in Central and Eastern European history dates back to his graduate school days.

Sam Ginsburg is a Przedbórz-phile and philatelist. His current major project is building a online family archive as a resource for his extended family.